The most honest art gallery in the world.

Highlights

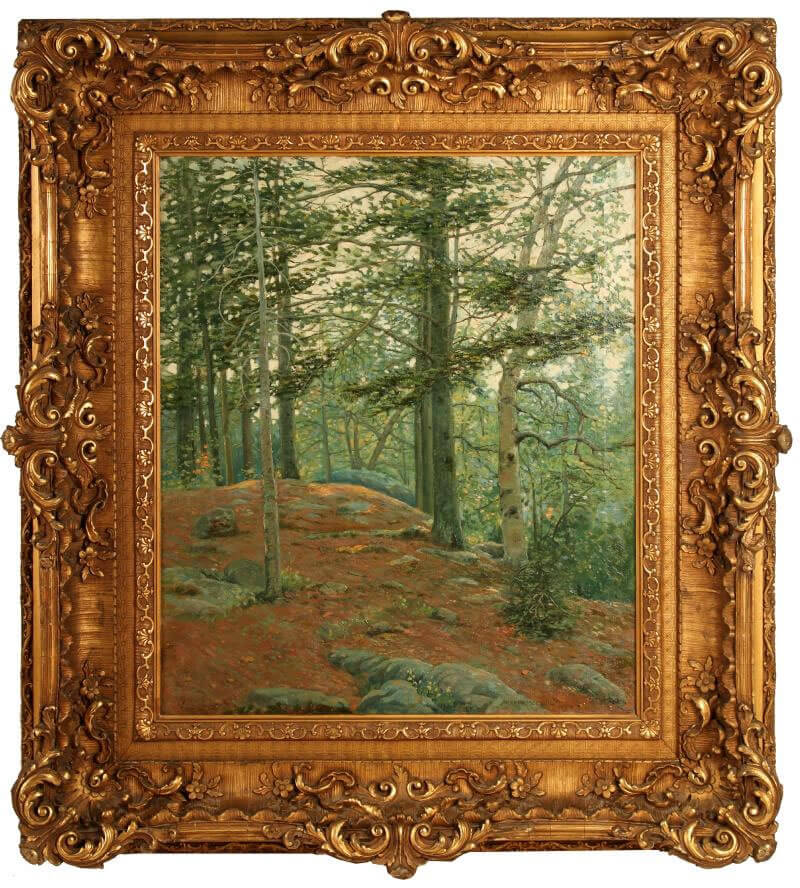

Arthur Barnet Hoeber (American Artist, 1854 – 1915)

In Arthur Hoeber Nutley loses one of those men whose busy lives of accomplishment never left them without time for endearing themselves to with whom they lived and worked. Nutley will miss Arthur Hoeber, especially that part who knew him as a friend and neighbor. In a larger way the town will miss him as one of those who spreads its reputation as the home town of men of talent and culture. – Nutley Sun, May-01-1915.

Born in Nutley, New Jersey in 1854, Hoeber, as a youth practiced drawing and sketching continually and working in watercolors. When he was just 14 years old, one of his watercolors was accepted at the American Water Color Society’s exhibition. So naturally, one would think, Hoeber’s first desire would be to become an artist. However, according to Charles H. Caffin in his 1903 article in The New England Magazine, what Hoeber really wanted to be was a soldier, but his shortsightedness (nearsightedness) precluded soldiering as a career option.

New York City is relatively close to Nutley and Hoeber found himself there when he was probably around 16 years old. It is uncertain whether he lived there or commuted from Nutley, but it is likely that he moved there as Caffin says, “he was at this time in business, studying meantime in the night schools of the Cooper Union.” He followed his study at the Cooper Union with study under J. Carroll Beckwith at the Art Students’ League.

His career as a professional artist apparently had not crystallized solidly just yet. Caffin believed that the young Hoeber may have wanted to pursue a career on the stage, as he had become friends with the leading New York stage actor of that time, Lester Wallack (1820-1888). Fortunately, Mr. Wallack steered Hoeber away from acting. Coincidentally, Wallack’s brother-in-law was English pre-Raphaelite artist Sir John Everett Millais (1826 – 1896) and Wallack provided Hoeber a letter of introduction to Millais, and off he went to London where he was kindly received by the artist. Millais, in turn, provided Hoeber letters of introduction to his friends in Paris and in the spring of 1881 Hoeber was in Paris at the Ecole des Beaux Arts studying under figurative painter Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904).

Hoeber’s first summer was spent in St. Valery, on the Normandy coast, “painting the peasants," and the following summer he completed “Sur la Grande Route,” which was exhibited in 1883 at the Paris Salon. Subsequent summers were also spent at the artist colonies in Normandy and at Concarneau and Pont Aven in Brittany. He shared a studio with expatriate artist Thomas Alexander Harrison (1853 – 1930) during their summer stays. During his time in France, Hoeber’s works were typically large paintings of peasants or fisher folk which were popular subjects in the French Salons at the time.

Hoeber spent six years in France, returning to New York City in 1886. He continued figure/genre painting after his return; however, perhaps it was the allure of the landscape backdrops to the peasants and fisherfolk that proved too strong, because in 1888 he switched to landscape painting sans figures, although a trip to St. Ives in Cornwall, England in 1893 found him painting both figures and landscapes. He spent his summers painting in Hyannisport on Cape Cod and Long Island, New York and the areas around Nutley, New Jersey. His oeuvre was tidal meadows and marshlands with their low flat horizons and the contrasting parallel sweeps of land and sky, depicted in the fading light of late afternoon or early evening. Although Hoeber eschewed the “modern” trends in painting such as Impressionism, his style often included elements among the Barbizon, Impressionist and Tonalist styles. His use of elements of each of these styles resulted in him being called a “semi-impressionist.” His works were vibrant and full of color.

In 1891 Hoeber settled in The Enclosure district of Nutley, New Jersey, where he built a combination house and studio. In his absence, Nutley had evolved into an artist’s colony. It was not far removed from New York City and a there was a railway station near his studio -- he was able to paint the quiet tidal marshes of New Jersey and return to New York as required. After the move to Nutley Hoeber started a sideline – he became an art critic for The New York Times, The New York Evening Globe, and The New York Journal and in all other major newspapers. These articles were written during the art season in New York – winters and early springs. Caffin says of Hoeber as an art critic, “he has filled the difficult role of painter criticizing the work of brother artists, with infinite discretion. It has helped that he is a man of kindly and generous impulses, incapable of pettiness, broad enough to enter into the points of view of other men, even if he cannot sympathize with them.”

His articles on art also appeared in Harper’s Weekly, International Studio, Bookman, Atlantic Monthly, Century magazines and American Art News. He was one of only two artists of that time who wrote on art – the other was Tonalist painter Birge Harrison, who was the subject of one of Hoeber’s articles. In addition to Harrison, Hoeber wrote a number of articles on important artists in history, including Sir John Everett Millais and Mary Cassat.

Considered one of Hoeber’s significant and important articles was “The New Departure in Parisian Art” which appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in December of 1890. which discussed “Meissonier’s breakaway group of the Societe Nationale des Beaux-Arts, organized against the traditional Salon system.” My favorite Hoeber articles is ”Concerning Our Ignorance of American Art” published in Volume 39, issue 3 of Forum Magazine (1908). Hoeber was despairing of American “art collectors”, referring primarily to wealthy businessmen who made their fortunes through the patronage of their fellow countrymen, but refuse their patronage of American artists, preferring instead to purchase often inferior European art, saying:

“These wealthy men pay fabulous sums for indifferent work by foreigners, work in many cases spurious, palpably so at that, and leave neglected at their doors men of talent, Americans who are making art history and whose works someday collectors will scramble for, paying prices out of all proportion to the needs of the workers living when patronage would have meant so much, both for physical and mental comfort.”

and:

“How is the average American house pictorially adorned? I am speaking of the houses of the well-to-do—not, of course, of those who cannot afford to buy something worthy for their walls. Well, there are some old pictures handed down from father or grandfather, a few engravings utterly uninteresting, and many photographs of the family. Perhaps a department store water-color or two, or an etching of the cheap variety, a photograph of a popular old master, or the interminable simpering Queen Louise coming down the stairs; and this last seems by some marvelous chance to have attracted a great majority of the public. But the pictures mean absolutely nothing, evince no taste or personality, and do not for a moment decorate the walls in the remotest manner. They just cover the wall paper.”

Yes, they just cover the wallpaper. Some people still “collect” art this way. Buy what you like, they are your walls after all, but I think Hoeber is gently reminding us to be a bit more discerning.

Hoeber penned a number of books also, including “Treasures of the Metropolitan Museum” (1899), “Painting in the Nineteenth Century in France, Italy, Spain and Belgium (1908),” and his final book, just before his death in 1915, “The Barbizon Painters: Being the Story of the Men of Thirty” (1915). It contains biographies of eight French artists who made art history in 1830s France. I recommend you read it.

Hoeber was both a talent writer as well as a talent artist, words flowed from his hand onto the page just as his paint flowed, expertly, onto the canvas. Again, I must quote Caffin, who was a contemporary of Hoeber:

One of the strong features of his {Hoeber’s} pictures is the excellence of his drawing, the suggestion of actual construction which he gives to his foregrounds and to the skies. This power is of the first importance in landscape and the last to which some painters, especially the younger ones, apply themselves. They feel themselves full of the sentiment of their subject, and try to reach straight out for it; relying, in fact, upon temperament, instead of upon the discipline of patient, thorough preparation in mastering the representation of objects. For it is the form and character of the form of each part of the scene that is, as it were, the scaffolding which supports the ornamentation of the sentiment. The latter is only so much flimsy drapery that would flop incontinently to the ground, if it had not the construction underneath to sustain it. And in one’s study of pictures it is not infrequently that one comes on instances of flopping sentiment.

Hoeber was a member of the National Academy of Design (Associate, 1909); Salmagundi Club (1900); and the Lotos Club and exhibited at Paris Salons (1883, 1885); National Academy of Design (1884 – 1900); Art Institute of Chicago (1890 – 91, 1894, 1904, 1913); Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1882-83, 1888-93, 1901-1915); Boston Art Club (1891-94); Pan-American Exposition (Buffalo, 1901, prize); and the Corcoran Gallery (1907 – 14).

In 1915, Arthur Hoeber died suddenly of heart failure while cranking his automobile in front of his home – he was 61. The citizens of Nutley, New Jersey missed Arthur Hoeber when he died, recognizing the loss of a man of talent and culture. After Hoeber’s death, the new Nutley Free Public Library was dedicated to the memory of Arthur Hoeber, with a specially designed bookcase that was to hold art books from Hoeber’s collection. In addition, Hoeber’s painting, “The Early Moon” was to be purchased to hang above the bookcase. So, if you see a Hoeber painting or read a Hoeber article or book, you will understand the loss.

Written by Joan Hawk, Researcher and Co-Owner Bedford Fine Art Gallery, March 18, 2025.

Use only with the permission of Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

References:

- American Art News 1915-05-01: Vol 13 Issue 30, Death of Arthur Hoeber.

- Baekeland, Frederick, 1991, Images of America: the painter's eye, 1833-1925, Birmingham, Ala. Birmingham Museum of Art in association with the University of Washington Press, Seattle and London.

- Caffin, Charles H., 1903, Arthur Hoeber – An Appreciation, in, The New England Magazine, 1903-04: Vol 28 Iss 2.

- Falk, Peter, ed., 1999, Who Was Who in American Art, Sound View Press, Madison, CT.

- Gerdts, William, H., 1980, American Impressionism, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle.

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/176970706/arthur-barnet-hoeber

- https/www.livingplaces.com/NJ/Essex_County/Nutley_Township/Enclosure_Historic_District.htmExcerpts from Enclosure Historic District

- https://newspaperarchive.com/nutley-sun-may-01-1915-p-3/

- http://nutleyhistory.nutleypubliclibrary.org/notable-nutley-authors/

- https://www.livingplaces.com/NJ/Essex_County/Nutley_Township/Enclosure_Historic_District.html

- The Forum January-March 1908: Vol 39 Issue 3, Concerning Our Ignorance of American Art by Arthur Hoeber, Forum Publishing Co., NY.

- Zellman, Michael, David, 1987, 300 Years of American Art, Volume I, pg. 477, Wellfleet Press.