The most honest art gallery in the world.

Highlights

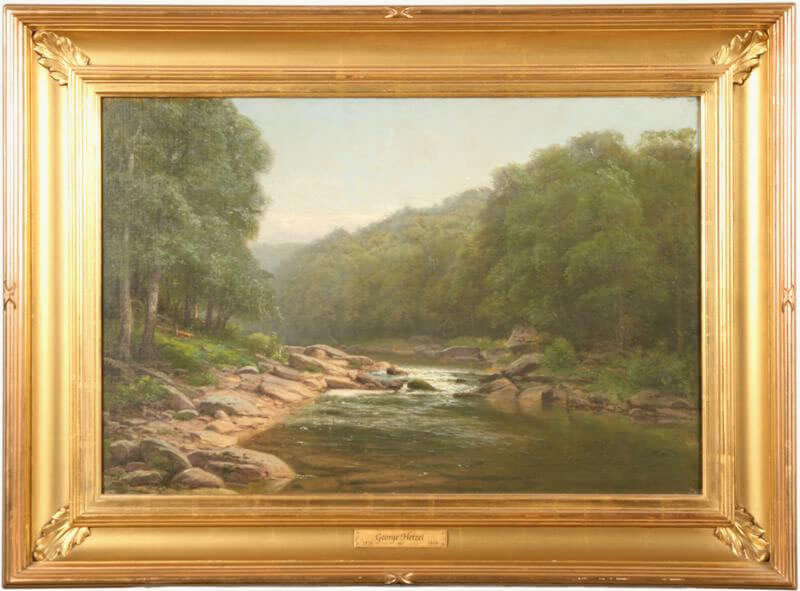

George Hetzel

George Hetzel

Mr. George Hetzel, above all else, is the “exponent of nature”, as we find it in Western Pennsylvania. He exhibits at least four of the most delightful examples of streams, with rocky basins, as they actually exist almost at our very doors. In this particular field, he has practically no equal hereabouts; to his brush alone has it been left to tell the story of most possibly the most striking phase of the landscape in the vicinity of the Alleghenies. -- Pittsburgh Dispatch, Feb 19, 1892.

Pittsburgh artist George Hetzel (1826 – 1899) was once described as being “inseparable from the woods.” His landscapes of the mountain streams of Cambria and Somerset counties near Scalp Level, Pennsylvania preserved, on canvas, the natural beauty of the rugged mountain streams of the Alleghenies -- a world apart from the smoky environs of industrial Pittsburgh. Paint Creek, Shade Creek and their tributaries, incised into the geologically ancient Allegheny Mountains, pristine and beautiful, were as yet unspoiled by the advance of industrialization that would overtake it by the end of the nineteenth century.

Who was this George Hetzel fellow who was to become the leader of the Scalp Level “school” of artists, and probably the most famous artist to ever visit the rural area of Scalp Level just outside of Johnstown, Pennsylvania? I’ll start at the beginning: George Hetzel was born in 1826 in Hangerviller, a village near Strasbourg in the Alsace region of France. Hetzel’s father moved the family to the United States, arriving at the Port of Baltimore in 1828, when George, Jr. was two years old. The family then had to make a long overland trek (there was no rail service or interstate highways then) to Brownville, Pennsylvania where they boarded a riverboat to Allegheny City, now the North Side of Pittsburgh. The trip that would now take roughly five hours by car today would have taken the Hetzel family days to make. Hetzel, Sr., who was a tailor by trade, had purchased a farm in Allegheny City and planted a vineyard there.

What was the path that led Hetzel, Jr., the son of a tailor and a vintner, down the path that would lead him to become one of Pittsburgh’s leading 19th century landscape painters? As a teen the young Hetzel worked in a rope-walk (a long, covered walk or building where long strands of hemp were manually twisted into ropes). We can surmise that this was not to his liking, as he soon left this job and became an apprentice to a house and sign painter, doing lettering and decorating commercial signs [Chew, 1994]. After about four years of doing this, he worked with a fresco painter decorating cabins and public rooms of riverboats and Pittsburgh saloons {Chew, 1994]. Hetzel also spent six months painting murals for the old Western Penitentiary, Pittsburgh. I wonder if any of the murals Hetzel painted remain there?

Hetzel’s father, recognizing talent in his young son, decided to send him to the art academy in Dusseldorf, Germany, so in 1847, he left decorating saloons, riverboats and penitentiaries behind and embarked on a trip to Dusseldorf. At the Academy, he took classes with figure and portrait painter Karl Ferdinand Sohn (1805 - 1867) and cityscape painter Rudolf Wiegmann (1804 - 1865). It is likely that he also studied with still life painter Johann Wilhelm Preyer (1803 – 1889) and landscape painter Caspar Johann Nepomuk Scheuren (1810 – 1887). In a short time, Hetzel had advanced beyond the typical rigorous academic training in drawing, anatomy, mixing oil paints and en plein air landscape painting that the Academy provided to beginning students, to the Meisterklasse (Masterclass) which meant that he could work on compositions of his own under the supervision of an Academy professor.

His first work, when he returned to Pittsburgh in 1849, was, again, decorating cabins of riverboats. But, before too long, he began receiving commissions for portraits and still lifes, and opened a studio on Fourth Avenue in Pittsburgh. An 1856 article referred to Hetzel as a “a painter of game...perhaps the first in the country.” Hetzel family lore has it that Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of Abraham Lincoln. purchased a small fruit still life by Hetzel prior to her husband’s election in 1860 as President of the United States. Hetzel’s still lifes of the early 1860s were simple tabletop arrangements of peaches, cantaloupes, that included grapes from his father’s vineyard. His fruit, fish and game still lifes hung in many of the finest dining rooms in Pittsburgh. Hetzel’s adherence to the principals of realism and naturalistic detail taught by the Academy prompted one of his contemporaries to comment that “I have more than once accompanied this quiet, modest artist among our best stores in quest of specimens of fruit and game in their season. Ah, how quickly did he scan them in all their details.”.

Although portraits and still lifes were Hetzel’s mainstay, landscape paintings of western Pennsylvania started cropping up in his oeuvre in the late 1850s. Hetzel traveled throughout Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia discovering forest interiors and streams that so captured his imagination that he committed them to canvas. “I drifted into landscape work, which was more in accord with my inclinations,”3 said Hetzel in 1896. This “drift” was probably hastened after the Civil War, when in 1866, friend and Pittsburgh artist Charles Linford invited him to go mountain fishing along with John Hampton, a lawyer for the Pennsylvania Railroad. [6, LaPlaca]. The spot was Scalp Level and the rest is history.

Hetzel was so taken with the area that the following year (1867) he convinced the entire faulty of the Pittsburgh School of Design to accompany him there the following summer to paint landscapes from nature. Three generations of the “Scalp Level School” traveled there every summer up to the turn of the century to sketch and paint en plein air picturesque scenes of the wooded streams of Cambria and Somerset counties. The horrific Johnstown Flood of 1889 interrupted this annual pilgrimage as the rail service from Pittsburgh into Johnstown was disrupted by the devastation. There were some forays into the area afterwards; however, the spell was broken. The geologic formations which made up the landscape that these artists painted, contained the seeds of its downfall – coal. Cambria and Somerset counties were to become the largest producers of bituminous coal of the twentieth century, coal that fueled the steel industries of both Johnstown and Pittsburgh. In the late 1800s, the Philadelphia-based coal company Berwind-Wind began buying up coal rights and property in the area, and in 1897, the company built the town of Windber (Berwind spelled backwards) at the confluence of Paint Creek and Little Paint creeks. In 1905, the company opened its underground mine, Eureka Mine 40, on the north side of Little Paint Creek. Scenic Scalp Level and the pristine mountain streams were gone. The canvases of George Hetzel and the other artists of the Scalp Level School are all that remain to document pre-mining Scalp Level.

During Hetzel’s lifetime he had experienced the “Great Pittsburgh Conflagration” of 1845, in which 56 acres of Pittsburgh were destroyed; the first Pennsylvania Railroad wood-burning locomotive to arrive in Pittsburgh (1852); the American Civil War (1861 – 1865) when Pittsburgh prepared itself for a Confederate attack; the building of the “new” Pittsburgh Courthouse (1888); the first telephone line between Pittsburgh and New York City (1891) and the opening of the Carnegie, Library, and Music Hall (1895). He had married Louisa Marie Siegrist in 1860, whom he had met during an excursion along the Juniata River at Lewistown. They had five children: James (1861), Charles (1863), Ella (1865), Frank (1870), and Lila (1873). A tragic railway accident in 1880 took the lives Charles and Ella, and severely injured James – a devastating loss for George and Louisa.

The Johnstown Flood and the start of mining that erased the magical charm Scalp Level was another loss for Hetzel. From his earlier peregrinations, He knew of other untouched areas in which to find intimate vignettes to put to canvas. In the 1850s and 1860s, he had painted scenes along the Conemaugh River, Juniata River (1850); Laurel Run in Mifflin County, (1860), Wilmington, Delaware (1872), Brandywine Creek (1872) and scenes at Saltsburg (Indiana Co., PA). In the summer following the Johnstown Flood, Hetzel was painting along the Connoquenessing and Slippery Rock creeks in Lawrence and Butler, counties, respectively and Linn Run (1898, Westmoreland County). Whether these localities offered the same magic as Scalp Level to him, we cannot know.

Just as the slow and ceaseless geologic processes continued to shape the landscape of the Allegheny Mountains, coal mining and emergence of the new town of Windber at confluence of Paint and Little Paint creeks permanently altered the landscape and streams at Scalp Level. It is ironic that the moldering ruins of abandoned of eighteenth and nineteenth centuries iron furnaces and sawmills that Hetzel had seen during his excursions along the Allegheny streams in the 1860s and 1870s, have been replaced by the imprint of another past industry, remnants of underground and surface mining, refuse piles and discolored, polluted water of the twentieth century. Another irony is that the name of the stream flowing through this area is named “Paint Creek,” named not because of the artists that visited there to paint, but because the rocks were naturally stained (“painted“) by the iron contained in the geologic strata of the area. This effect was exacerbated by mining activities. It is fortunate that Hetzel, a man “inseparable from the woods,” did not live to see his beautiful Scalp Level become a palimpsest, an art term meaning any painting that has been reused by painting over it. Scalp Level, a painting designed by nature, was indeed indelibly painted over by less skilled “artists.”

Nothing is immutable and as the Scalp Level landscape evolved, so too did Hetzel’s oeuvre and style, – a portraitist, a still life painter, and finally, a landscape painter. Hetzel’s style of painting changed also. His early landscapes reflect the detailed realism and chiaroscuro (the use of light and dark to achieve mass and dramatic three-dimensional effects) stressed at the Dusseldorf Academy (Chew, 1994) and that of the influence of the American Hudson River School artists, with whom he was acquainted. A visit to France in 1879 and his admiration for work of the French Barbizon painters Jean-Francois Millet and Camille Corot2 [4, James A. Israel], likely influenced his later looser brushwork and handling of color, moving beyond the dense interior forest streams to more open views with a lighter palette.

Although landscapes dominated his oeuvre from circa 1860, Hetzel continued to paint still lifes up until the time of his death in 1899, although they were painted with looser brushwork and included bric-a-brac in the 1870s-- a departure from his earlier still lifes. When the Pittsburgh School of Design for Woman opened in 1865, Hetzel taught a class in landscape painting. It is notable that he included the women enrolled at the school to join the summer Scalp Level excursions – chaperoned, of course! Mrs. Andrew Carnegie was a chaperone one summer. In 1887 Hetzel, along with another Scalp Leve artist John Beatty, founded the Pittsburgh Art School which existed until 1896.

Although George Hetzel may be considered a regional artist, associated with the Scalp level School, unlike many of his colleagues, he was well-known for his landscapes beyond Pittsburgh. In Pittsburgh, he exhibited his work at J. J. Gillespie’s, a well-known gathering place for Pittsburgh’s artists, and at Wunderly Galleries. He also had his paintings accepted at the larger and more prominent venues -- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia (1855 - 69, 1876 – 81, 1885, and 1891); Pittsburgh Sanitary Fair during the Civil War to raise funds to support the troops (1864); National Academy of Design in New York City (1865 -1882); Corcoran Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., 1880); Union League Club (New York City, 1880); Saint Louis Exhibition (Missouri, 1880); Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition (1893); first annual International Exhibition of the Carnegie Institute (1896).

The original magic of Scalp Level still lives through the paintings of George Hetzel, located in the collections of major museums and private owners, who appreciate his skill and beautiful renderings of places that no longer exist. As a postscript, there are recent efforts underway to reclaim and restore these Allegheny Mountain streams to their pristine, natural beauty, to become, once again, the streams that George Hetzel and the Scalp Level school artists fished in and along which they set up their easels and painted.

Written by Joan Hawk, Researcher and Co-Owner Bedford Fine Art Gallery, March 18, 2025.

Use only with the permission of Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Selected bibliography

Chew, Paul, A., ed., 1989, Southwestern Pennsylvania Painters, Collection of Westmoreland Museum of Art, George Hetzel Retrospective and The Scalp level Artists Exhibition, 26 March – May 8, 1994, Westmoreland Museum of Art, Greensburg, Pa.

Chew, Paul, A., 1994, Geo. Hetzel and the Scalp Level Tradition, George Hetzel Retrospective and The Scalp level Artists Exhibition, 26 March – May 8, 1994, Westmoreland Museum of Art, Greensburg, Pa.

Danly, Susan and Bruce Weber, 1998, For Beauty and For Truth: The William and Abigail Gerdts collection of American still life, Amherst, Mass.: Mead Art Museum, Amherst College; New York, N.Y.: Berry-Hill Galleries.

Falk, Peter, ed., 1999, Who Was Who in American Art, Sound View Press, Madison, CT.

https://newspaperarchive.com/pittsburgh-dispatch-feb-19-1892-p-4/

Israel, James A., “Art in Pittsburgh,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, December 20, 1896, p. 12, in, “American Paintings and Sculpture to 1945 in the Carnegie Museum of Art,” Diana Strazdes, 1992, pp. 244-252.

LaPlaca, Jaclyn, 2003, Somerset County: pride beyond the mountains, Arcadia, Charleston, SC.

Merriman, Woodene, ed., Better Living, in, Pittsburgh Post Gazette, Monday, Feb. 6, 1978, “Portraits by Father and Daughter” at the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania.

Strazdes, Diana J., 1992, American paintings and sculpture to 1945 in the Carnegie Museum of Art, New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Museum: Distributed by National Book Network.

Cosmopolitan Art Journal 1856, p. 15, in, Avery, Kevin J., Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, John K. Howat, Doreen Bolger Burke, and Catherine Hoover Voorsanger, 1987, American Paradise: The World pf the Hudson River School, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York published in conjunction with the exhibition, October 4, 1987 – January 3, 1988.

Way, Agnes, c. 1870-1935, Scrapbook of Newspaper Cuttings Collected by Agnes Way.

Youngner, Rina, C. 2006, Industry in Art: Pittsburgh, 1812 – 1920, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA.